Is a magnet test enough to identify a part — or does that belief shortchange your project?

This introduction clears the confusion: stainless steel is a family of iron-based alloys, not a single material. Chromium forms a passive film that gives corrosion resistance, while the material’s microstructure decides magnetic behavior.

Some grades are magnetic by design: ferritic and martensitic families show attraction. Austenitic types—like 304 and 316—are usually non-magnetic unless cold worked or welded, which can introduce ferrite and change permeability.

For homeowners and metal workers, the difference matters: a quick magnet check helps sorting and inspection but does not prove grade or quality. Choose a grade by balancing corrosion resistance, required magnetic response, and fabrication plans.

Ask yourself: where will magnetic response affect inspection, assembly, or in-service performance? Define that need first—then pick the proper grade and process.

Stainless steel basics and what drives magnetism

Understanding why certain alloys attract a magnet starts with composition and crystal form.

How composition defines corrosion resistance

An alloy becomes corrosion resistant once it has at least 10.5% chromium and low carbon levels (about 1.2% max). Chromium forms a thin passive film that helps the surface self-repair after scratches, which is the core of corrosion resistance.

Crystal structure 101

Crystal structure controls magnetic behavior. Austenite (face-centered cubic) is usually non-magnetic. Ferrite and martensite (body-centered forms) are ferromagnetic and show attraction.

Why iron alone doesn’t decide magnetic response

Many alloys contain iron, yet magnetic pull depends on phase, not just iron content. Nickel stabilizes austenite; that is why common household grades like 304 and 316 stay non-magnetic when annealed.

Separating corrosion resistance from magnetism

- Chromium, with additions like molybdenum, controls pitting resistance.

- Structure controls permeability and magnetic response.

- Processing—cold work or welding—can change phases after fabrication.

Rule of thumb: choose austenitic types for non-magnetic needs; pick ferritic or martensitic grades for strong pull. When magnetism is critical, specify acceptable permeability and consult the magnet test limits at magnet test limits.

Which stainless steels are magnetic? Families, grades, and crystal structure

Different alloy families show distinct magnetic behavior based on their crystal phases and composition. That makes family choice the quickest clue to magnetic response.

Austenitic grades — notably 304 and 316 — are usually non-magnetic when annealed. Nickel stabilizes the austenitic crystal, so parts resist attraction. Cold forming or heavy bending can create local martensite and produce partial magnetic spots near bends.

Ferritic options such as 430 owe attraction to ferrite content. These steels are magnetic, cost-effective, and offer moderate corrosion resistance for indoor and mild environments.

Martensitic grades like 410, 420, and 440 are magnetic and hardenable. They suit knives, wear parts, and tools where edge retention and hardness matter.

- Duplex (for example 2205) mixes austenite and ferrite — expect noticeable pull due to the ferritic fraction.

- Precipitation-hardening grades gain magnetism after aging or hardening — useful when strength and predictable magnetic behavior are needed.

Remember: magnetic response does not predict corrosion performance — 316 resists chlorides far better than 430 despite lower attraction. For verification, use a magnet and, when critical, a permeability meter or consult the magnet test limits.

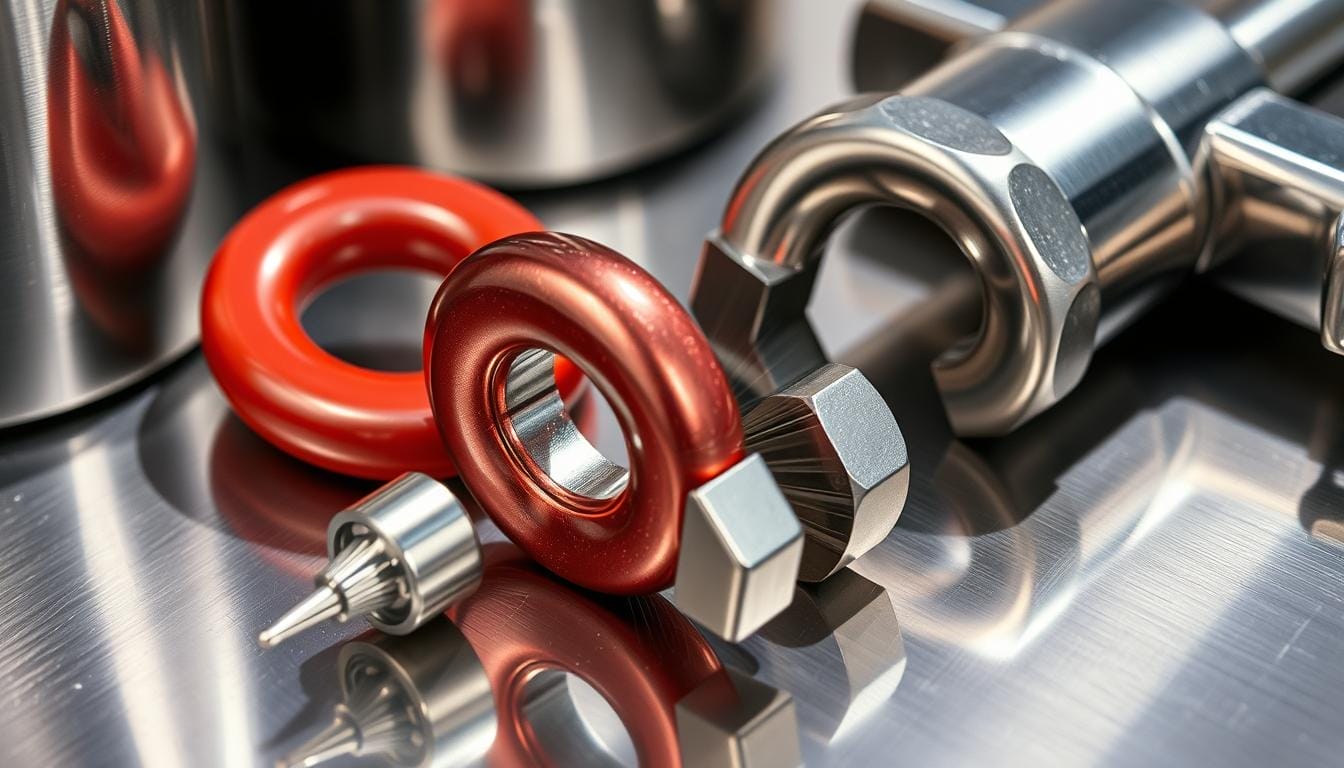

stainless steel and magnets in real-world use

Processing often dictates how a part will react to a magnet in service. Work steps can change local phases and move permeability enough to matter for inspection and function.

Processing effects: cold forming and welding can change permeability

Cold work—bending, deep drawing, and heavy forming—can convert austenite into martensite. That creates zones with higher magnetic pull after forming.

Welding adds heat and may introduce ferrite near the join. The heat-affected zone often shows different permeability than the parent material.

Manufacturing implications: welding arcs, magnetic fields, and quality

Magnetic material near a weld can cause arc blow and erratic current paths. That reduces weld quality unless operators control joint fit-up and grounding.

- Measure stray magnetic field with a gaussmeter when precision matters.

- Reposition clamps and change work orientation to limit arc deflection.

- Specify acceptable permeability for critical parts used in the medical or research industry.

Everyday testing: the “magnet test” and its limits

The magnet test is quick for shop sorting but not definitive. Cold work and welding can change a part after the initial check.

Practical example: a 304 stainless sink shows little pull on the flat drainer but stronger attraction at pressed bowl corners due to forming. That simple case illustrates phase change in routine fabrication.

For critical non-magnetic needs—MRI rooms, sensors—specify a maximum permeability and confirm with instruments. For guidance on testing and limits, consult this resource on stainless steel magnetic.

Practical takeaways for choosing the right stainless steel grade today

Start with environment and function: list corrosive agents first—chlorides, humidity, cleaners—then match corrosion resistance using chromium and, where needed, molybdenum.

Choose the family by role: austenitic options (304, 316) give high corrosion resistance with low magnetism when annealed. Ferritic and martensitic choices deliver stronger magnetic response and different corrosion profiles. Duplex offers strength with noticeable pull.

Specify performance, not just a name: include exact grades, maximum magnetic permeability, and fabrication controls. Expect forming or welding to change crystal structure—plan inspections post-process. For detail on nickel content, see the page that contains nickel.

Ask: where does magnetic response matter most—function, safety, or manufacture? Answer that and let it decide the final grade and acceptance criteria.